Blog

Challenge for All Blog - Autumn 2024

Andrew Taylor - Primary Senior Teaching and Learning Consultant

Where Have the More Able Gone?

Nowhere!

Whilst there has been encouragement to use the terminology of 'more able' less in recent years, the fact that every class includes children who are comparatively quicker at learning new things than other children means that they still exist and need to be catered for. How we refer to these children (high prior attainers, rapid graspers, high learning potential, more able etc.) really does not matter as long as there is a common understanding of what the terminology means in your school and how teaching may need to be adapted to meet their needs effectively.

Ofsted's current inspection framework does not name 'more/most able' as a specific group but emphasises 'all pupils' when referring to the quality of education provided by the school. In some inspection reports from the last two years, most able pupils have been mentioned, for example,

"Teachers expertly deliver the curriculum through activities that spark pupils’ interests and

match the intended curriculum outcomes. Pupils, including the most able, are regularly

challenged to deepen their learning through thoughtfully designed activities."

Inspection Report, Clayton-le-Woods Manor Road Primary School, June 2023

As this example illustrates, it is imperative that the challenge for all children is carefully considered and then implemented during each lesson.

The way in which challenge is provided starts with having an ambitious curriculum for all children. The specific strategies for challenge may vary depending on the subject and it is vital that there is a common understanding of how children can be stretched and challenged in all subjects across the curriculum.

However, all children require challenge and to experience 'struggle' so senior leaders, subject leaders and teachers need to be aware of what is expected for all children and what a deeper expectation of that learning would look like for some children.

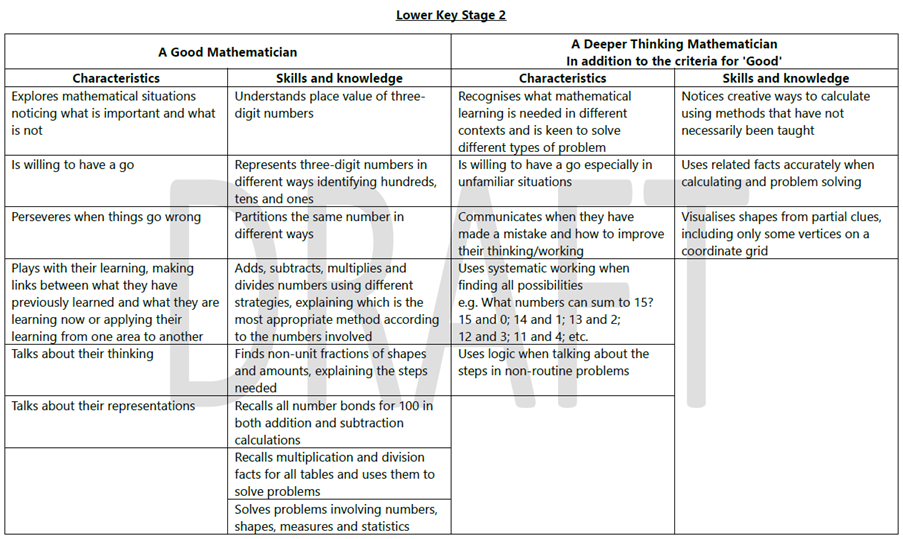

The Maths Team here at LPDS have been exploring the idea of trying to define what a deeper thinking mathematician might look like. In order to do this we had to go back and try to define what a good mathematician might look like, and this being the expectation for all children – we want all children to be good mathematicians. This is a combination of knowledge, skills and characteristics, which we have adapted from our Key Learning and the Characteristics of Effective Teaching and Learning from the EYFS Framework. Once we had determined the features of a good mathematician, we were able to discuss and suggest knowledge, skills and characteristics of a deeper thinking mathematician.

Here is an example of what it might look like for Lower Key Stage 2:

Once a framework such as this is in place, then teachers can be more aware of the learning experiences children require to develop into a 'good' or even a 'deeper thinking' mathematician.

This could in turn feed into school assessment systems where trackers may include children who are deemed to be better than expected but these can now be identified more accurately using criteria that has been created with the whole staff and learning experiences that allow children to demonstrate the knowledge, skills and characteristics that have been agreed.

If this interests you then you can join in with further discussions around stretch and challenge for all in our termly network meetings, where we will be expanding on this work as well as sharing other advice and support for this area https://www.lancashire.gov.uk/lpds/courses/?subject=ABL

If you would like specific support around stretch and challenge in any particular subject then get in touch with our senior consultants to arrange bespoke support for your school:

Mathematics: Lynsey.norris@lancashire.gov.uk

English: Nicola.martin@lancashire.gov.uk

Science and Foundation Subjects: Andrew.taylor@lancashire.gov.uk

Great Teaching Blog - Autumn 2024

Jen Little – Teaching and Learning Consultant and Assistant Headteacher and Y6 Teacher

Creating a Positive Learning Culture

Guy Claxton states:

“Students, who are more confident of their own learning ability, learn faster and learn better. They concentrate more, think harder and find learning more enjoyable. They do better in their tests and external examinations. And they are easier and more satisfying to teach.” (https://www.buildinglearningpower.com/)

How do we create children who are confident in their own learning? In this blog I will share some of the strategies I have found to be effective in my own practice.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a useful place to start. It will be difficult to develop learning behaviours if children's basic needs are not met and if our classrooms do not provide a culture in which children feel safe to experiment, and comfortable to take risks. The children in our classes need to feel emotionally safe, liked, and valued members of the class, and school, community.

When starting a new school year, my priorities are to build positive relationships with every member of my class; to create a safe space; to know what makes each child'tick' and, above all, to develop a level of trust.

“There is a strong evidence base that teacher-pupil relationships are key to good pupil behaviour and that these relationships can affect pupil effort and academic attainment” (Improving Behaviour in Schools: EEF p. 10)

What motivates your children – both in school and out of school? What affects their confidence? What is their favourite book/sport/colour? Be interested! I like to do an ‘All About Me’ book on the first day of a new school year. On the surface it is a book with a page about each child but, in reality, it gives me an insight into their lives. ‘Draw a picture of your family’ may seem like a simple task, but this often opens the door for conversations about who lives where, and how often they see the various members of their family. This means that, when a child says, “I’m going to my dad’s tonight”, I understand the enormity of that statement for that particular child and the possible emotional impact in the build-up to, or following, that visit.

I also make it a point to find out when each child's birthday is so I can wish them a happy birthday. I get everyone in my class a birthday card and write a little message in there, to let them know that they are cared for and thought about. (Most supermarkets do a great range of budget birthday cards). Taking interest, showing care and kindness, having empathy for each child starts to create a culture of trust that is key in the learning process. We know, from research about the brain, that trauma can have a significant impact on child development – cognitively and emotionally. Building trusting relationships with adults in school is paramount if we are to help them progress through Maslow's levels to self-actualisation.

Building positive relationships and creating that trust begins with these initial interactions with children and is vitally important. However, it can sometimes be hard - especially with children who present challenging behaviour. They need to know that you are 'on their side', that this year is perhaps 'a fresh start, a clean page'. That is not to say that we do not have high expectations, boundaries and routines. But consideration of the language we use can have a huge impact on how children respond to these. Using positive phrasing can be a genuine motivator for children. For example instead of “Stop talking!” etc, I find it helpful to rephrase it as, “I'm looking to see who is ready to learn”. 'Catching them being good' is so important, acknowledging and praising the behaviours you want to see. For example, "I can see Bobby is ready to listen to me – that shows good learning,' not only makes that child feel valued but encourages other children to behave in the same way. In fact, using positive, specific praise has the potential to increase on task behaviour significantly.

“Over the two-month study, pupils increased their on-task behaviour by an average of 12 minutes per hour (or an hour per day), while pupils in similar comparison classes did not change their behaviour. This study implies that teachers with disruptive classes could benefit from increasing their positive interactions with pupils.” (Improving Behaviour in Schools: EEF p. 27)

Carol Dweck (a professor at Stanford University) led a study about praise, looking at the differing impacts of praising achievement vs effort. All children in the experiment (400 students from across the USA) were given a very simple IQ test. Half the children who took the test were praised for their intelligence e.g. ‘You must be really smart’. The other half were praised for their effort ‘You must have worked really hard at this’. This seems a subtle difference, but the impact of these subtleties was incredible. All children were told that they had to take another test but this time they were given an option of a) A harder test – a greater opportunity to learn and grow; or b) An easy test – you will surely do well on this one. The results? 67% of the children who were praised for their intelligence chose the easier test whereas 92% of the children who were praised for their effort chose the harder test. An incredible difference, I’m sure that you’ll agree.

Dweck goes on to conclude that the “The child (praised for intelligence) hears ‘Oh you think I’m brilliant and talented. That’s why you admire me…I'd better not do anything that will disprove this evaluation”. As a result, Dweck says that these children are likely to “enter a fixed mindset, they play it safe in the future and they limit the growth of their talent.” In contrast to this, focussing on the effort that you put in and the chance to grow ‘they don’t feel that if they make a mistake that you won’t think that they are talented. Instead, these children think ‘if I don’t take on hard things and stick to them, I’m not going to grow.’ This is a strong indicator of the type of feedback we need to be giving to our children whether verbal or written and where, as adults in the classroom, we should focus our praise. (https://teaching.temple.edu/sites/teaching/files/resource/pdf/Dweck-Perils%20%26%20Promises%20of%20Praise.pdf)

Another aspect of developing a culture for learning is to use the language of 'learning' rather than 'doing'. I endeavour to be a facilitator of learning – teaching children to take responsibility for their own learning - often through open-ended questions and learning activities. Children are celebrated for their approaches to learning not just their successes in learning. These subtle shifts help to change how the children feel about themselves as learners - which can only be beneficial in the future.

Sharing with the children how we learn is another key to creating an effective culture for learning. In fact, the EEF study into metacognition finds that metacognitive learning and self-regulation have the potential to add an additional 7 months progress a year (https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/teaching-learning-toolkit) . For me, part of this process is sharing with the children the cognitive psychology about changing and growing their schemata and talking to the children about what makes a good learner, the behaviours that they will need to grow their learning and praising them for practising these behaviours. Some schools attribute learning behaviours to animal characters (e.g., resilience = tortoise) or some schools create learning superheroes (resilience = The Hulk). However this is approached, it needs to be consistent throughout school and the learning behaviours need to be explicitly taught. It is then important to ‘catch' the children displaying these behaviours and draw their attention to this. E.g. ‘I really like the way that you made a connection between x and y. Good learners make connections.’ ‘I could see that you struggled with this calculation at first but you kept on going and used your hundred square to help you – that shows resilience and learning choices.’

Colleagues in EYFS are very skillful in identifying and creating activities which promote the characteristics of effective learning but, so often, these types of learning opportunities are limited to the Early Years.

Giving children regular opportunities to flex these learning muscles throughout school is key to them developing life-long learning behaviours and habits. (A future article will explore explicit teaching of learning behaviours more fully.)

Another key part of the 'settling in' process, is the establishment of expectations and routines. This can range from where we put the scissors when we are finished with them, to where the hundred squares live, to how I expect a piece of work to be set out, to how we line up etc. Showing the children explicitly how I want this to be done is vital, in my opinion, to the calm and smooth day to day running of the classroom. Consistency, in my experience, is crucial, ensuring that my expectations are in line with other teachers in school and then sticking to them. Forgetting to underline the date, or leaving a pen without its lid on, may seem inconsequential, however the children need to know that I expect these things to happen every time. And that does not mean that I berate the child who has forgotten to do one of these things, it is a reminder and then a ‘Thank you’ for carrying out the required action.

The DFE Guidance 'Behaviour in schools: Advice for headteachers and school staff' states,

'Routines should be used to teach and reinforce the behaviours expected of all pupils. Repeated practices promote the values of the school, positive behavioural norms, and certainty on the consequences of unacceptable behaviour.

Any aspect of behaviour expected from pupils should be made into a commonly understood routine, for example, entering class or clearing tables at lunchtime. These routines should be simple for everyone to understand and follow.'

Consistency and predictability are often cited as crucial for developing positive behaviour for learning, however, the DFE guidance also recognises that,

' Adjustments can be made to routines for pupils with additional needs, where appropriate and reasonable, to ensure all pupils can meet behavioural expectations.' (p. 11 points 20-21)

In Paul Dix’s book “When Adults Change, Everything Changes", he quotes Haim Ginott (a school teacher, a child psychologist, a psychotherapist and a parent educator) who says,

“I have come to the frightening conclusion. I am the decisive element in the classroom”.

In my opinion, no truer word has been spoken. We are so often the masters of our own destinies and influencers of those of the children in our classes. Our expectations; the relationships we build; the models we present; the routines we establish; the language we use; the ways in which we act, and react, impact hugely on the learning culture within our classrooms and, ultimately, on the learning and progress of the children in our classes. This is the time to be 'investing' in all of the above to ensure a happy classroom culture for learning is established and maintained throughout the academic year.

Newsletter

Physical Education Blog - November 2022

Jen Little – Teaching and Learning Consultant and Assistant Headteacher and Y6 Teacher

School Swimming

By the time a child is ready to leave primary school they should be able to swim, know how to get out of trouble if they fall into water, know the dangers of water and understand how to stay safe when playing in and around it.

It is part of the national curriculum PE programme of study for England, so all local authority-maintained primary schools must provide swimming and water safety instruction. Schools have a statutory obligation to teach swimming and water safety to all pupils during Key Stage 1 or Key Stage 2

The national curriculum sets out three outcomes which all pupils must be able to demonstrate they can meet before they leave Year 6.

It is important that all pupils are supported to meet these requirements before they leave primary school. This includes those with special educational needs, those with a disability or impairment and those whose first language is not English.

The overall aim of primary school swimming and water safety instruction is to introduce children to the water - particularly those who may not have already been in a swimming pool or had lessons. The emphasis is on ensuring all pupils have the basic skills to be able to enjoy the water safely and know how to safe self- rescue if the worst happens.

The three national curriculum requirements

The minimum requirement is that, by the time they are ready to leave Key Stage 2, every child is able to:

• swim competently, confidently and proficiently over a distance of at least 25 metres

• use a range of strokes effectively

• perform safe self-rescue in different water-based situations(1)

It is expected that many pupils will achieve more than these minimum expectations. Therefore, school swimming programmes should also provide opportunities for these pupils to further develop their confidence and water skills.

This year’s Sports Premium Funding can be used to fund the professional development and training that are available to schools to train staff to support high quality swimming and water safety lessons for their pupils. In Lancashire we offer two options.

1. The LPDS Getting to Grips with School Swimming 1 day course

2. The Swim England Support Teacher of School Swimming Award, this requires up to 8 hours online learning prior to attending the Swim England practical day.

Both of these CPD courses will be bookable via the LPDS website PE courses.

Details - LPDS Resources (lancashire.gov.uk)

The premium may also be used to provide additional top-up swimming lessons to pupils who have not been able to meet the national curriculum requirements for swimming and water safety after the delivery of core swimming and water safety lessons. At the end of key stage 2 all pupils are expected to be able to swim confidently and know how to be safe in and around water.

Schools are required to publish information on the percentage of their pupils in year 6 who met each of the 3 swimming and water safety national curriculum requirements

Primary School and Accompanying Teachers/Adults

• It is suggested guidance that a minimum of two members of school staff should accompany children swimming: a School Teacher, HLTA or TA. This will be dependent on the cohort of children and the needs within each class.

• The school is accountable for their pupils’ attainment and progress. Therefore, regular dialogue should take place between school teachers and swimming teachers to ensure both are aware of the progress made.

• The school should be aware and agree the overall programme and lesson plans to ensure they fit with the national curriculum requirements.

• School teachers are required to provide up-to-date, accurate registers of those attending the lessons. They should also advise about any individual medical treatment needs or special requirements.

• School teachers are responsible for highlighting any concerns about the pace or content of the lessons, and how the pupils are responding.

• School teachers/accompanying teaching assistants/support staff are responsible for general order and discipline. Together, they should maintain high levels of supervision in the changing rooms, on poolside and while pupils are in the water.

• School staff should play an active role supporting learning and dealing with behaviour and welfare issues.

• At the end of each lesson, the school teacher should discuss the progress made by the class and report back to the school/parents.

• At the end of the swimming programme, schools must publish details of

how many pupils within their year 6 cohort have met the national curriculum requirements. Therefore, good communication between the swimming teacher/ provider is important.

Schools must ask to see the SLA (service level agreement) from the pool prior to school swimming sessions and school should meet with swimming providers prior to each academic year to discuss the expectations from the school with the service the pool provider is offering.

Assessing progress and attainment

School teachers are accountable for pupils’ attainment, progress and outcomes(2). Therefore, the school teacher should be aware of what their pupils are doing at all times, how well they are progressing and what they need to do next in their learning.

To support teachers to do this, regular and frequent dialogue should take place between school teachers and swimming teachers. This helps to ensure both parties are aware of what the pupils are being taught and what they are learning. This could be recorded by the provider and shared with the school, or the school teacher could record the progress directly at the end of each lesson. There are

In Lancashire we are adding our new Swim England Swim Charter Lesson Plans to the Lancashire PE Passport App to support the teaching and learning of school swimming.

Swim Refusal

There are a growing number of children and families who are refusing to swim. Ultimately parents do not have the choice. Schools must deal with each case sensitively and try to establish the reason behind individuals not wanting to partake and act upon this.

Lancashire Legal Services suggest …

School must reiterate it is a statutory part of the national curriculum as is English maths and science lessons so parents can't withdraw their children from it. It is not the parents’ choice; it is the responsibility of the school.

Schools must keep explaining the benefits to the parents and keep encouraging them to participate .

If children fail to attend then it will unfortunately be classed as an unauthorised absence unless there is a certified medical exemption relating to the child themselves which could ultimately result in fines

Try…

First try to attempt each week to talk the pupil round – this could be with a swimming kit that school provides – and then the consequence put in place if the child refuses to get changed/go in the pool.

Schools approach this in the same way they would if a child was refusing to do maths or science. By this stage we would probably be recommending consequences in line with the behaviour policy – perhaps completing a project – why it's important to learn to swim.

Children must attend the pool and the consequence takes place each week the child refuses to get in the pool.

We need to be very clear to the parents that their child is to go swimming and refusing is not an option.

However, if parents produce a doctor’s note stating the school swimming is making the child ill and it is backed up with a medical reason we then have to follow the medical guidance from the GP.

We have further guidance on the LPDS website, PE Subject Leader section